Introduction

“We must focus on what the student does while learning, what role the student adopts and how the student interacts not only with the learning input, but also how the student thinks about feels about learning and to how the social environment mediates and determines the quality of learning” (Nicol, 1997, p. 1, as cited in Jacques and Salmon, 2007, p. 50).

Before embarking on a study of the learner journey, it would be prudent to establish the definition of ‘learning’. Curry (1983, p. 2) states that learning is both a process and a product and that it is adaptive, future focused; and holistic; affecting an individual’s cognitive; affective; social, and moral volitional skills, observable as a relatively permanent change in behaviour, or potential behaviour, and observable in the improved ability of the individual to adapt to environmental stimuli. Over the past 30 years, the nature of learning has been the subject of much study and debate, influencing teaching practices in education by shifting the focus away from the activities of the teacher (that is, the transmission model) transferring to those of the learner (Jacques and Salmon, 2007, p. 50).

Having considered teaching practice in the first paper and how the use of BSL/English Interpreters impacts on such teaching practice in the second paper, it is time to examine the learner journey in relation to my teaching practice and the use of BSL/English Interpreters in their learning. It is proposed to do so by exploring learners’ experiences of my lectures and workshops, and extending this to cover the likely experience of learners’ using any new approaches identified and any technology-advanced pedagogy, as well as the use of BSL/English Interpreters in my teaching. The aim is to determine the learning experiences (and likely experiences) of my students.

In order to do so, this paper has been split into four sections: understanding learners, in which student profiles and motivations will be examined to establish exactly who or what we are dealing with in higher education; understanding learning, whereby there will be an exploration of the three main learning theories and how they have been demonstrated in my teaching practice; what learning styles exist and how they can be useful to both students and teachers alike; the various types of learning that have been utilised in my modules or that I would like to try; and finally the impact using BSL/English Interpreters has had on my teaching practice from the point of view of students themselves.

Understanding learners

Careful consideration of the characteristics of the learners allows lecturers to create instruction that is both effective for and appealing to the learners (Schwartz, 2001, p. 386). In other words, before any consideration can be given to what teaching methods and materials best suit students, it is necessary to consider what their profile and motivations are likely to be.

Profile of learners

Learning groups are much more diverse than 30 years ago, and therefore, any approach to learning design needs to focus on a wider range of needs and styles of contribution; in other words, a cross-cultural perspective is needed (Jacques and Salmon, 2007, p. 51). A learner profile of the modules I taught in the academic year 2014/15 can be found at Appendix 1.

When considering the characteristics of students, teachers are likely to refer to student orientations and their consequent motivations, differing levels of maturity, study methods, cognitive style and personality differences and physiological differences and less likely to refer to the differences in ability or intelligence, in relation to their success (Beard and Senior, 1980, p. 20). It is clear, therefore, that strictly speaking, the innate ability or intelligence of learners is not the be all and end all, and that effective and interesting teaching methods will play an important part in the extent to which students commit themselves to a course (Beard and Senior, 1980, p. 19). Indeed, Beard and Senior (1980, p. 54) state: “Motivating students demands a knowledge of individuals and their needs in addition to knowledge of teaching methods and psychologists’’ findings about motivation”.

Motivation is commonly perceived as being either intrinsic or extrinsic, and Eble (1988, p. 182) argues that the teacher needs to take advantage of extrinsic motivations (such as getting a job at a high rate of pay in an interesting line of work) as exist and hope to provide an atmosphere in which intrinsic motivation becomes more important. Lewin (1952, as cited in Beard and Senior, 1980, p. 3) states that it is the various groups to which an individual belongs that will determine his beliefs and ideologies. Bruner (1966, as cited in Beard and Senior, 1980, p. 3) argues that learning in itself is an intrinsic motivation which finds both its source and its reward in its own exercise, and that lack of motivation is likely to be a problem when learning is imposed on the learner when the teacher fails to enlist his natural curiosity, seeming irrelevant or inappropriate to his needs, or the learning required is at a level which makes achievement of competence impossible.

Generally speaking, my students are a mixture of traditional undergraduate school-leavers, postgraduates who have just completed a degree, and professionals. Most are literate and are required to apply the theories they learn to problem scenarios, that is, the law and how it relates to particular situations, as irrespective of their background, they all studied law in some shape or form. Students coming into higher education will differ in their reasons for doing so; this is known as their learning orientation, and they will have either an extrinsic (that is, educational progression) or intrinsic (an intellectual interest in the discipline studied) interest in the course they are studying (Marton et al, 1997, p. 17.).

While this data is not available to reach a determinable conclusion as to my students’ learning orientation, it is surmised that the majority studying Employment Law intend to have a career of some sort in the legal profession as it is recognised as a qualifying law degree for professional purposes in the UK (University of South Wales, no date), with those on the Master of Laws (Legal Practice) (MLaw) programme aiming to become solicitors (MLaw is a four-year degree combining the LLB Law and the postgraduate Legal Practice Course), therefore students are more likely to have an extrinsic approach.

Corporate and Business Law is a module that counts towards an accountancy qualification with the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, so it is assumed that the students completing this module aim to become qualified accountants, and are therefore again more likely to have an extrinsic approach. Corporate Law is a Masters-level module, and it is assumed that students who studied this module did so for intrinsic reasons as this course does not generally fit in with particular career paths, although some students may simply wish to attain a Masters-level qualification to further their careers. At least one of them has expressed an interest in going on to do a PhD, suggesting that he, at least, has an extrinsic motivation.

It is difficult to ascertain the motivations of Law for Managers students as they would have studied this module on a range of undergraduate business degree programmes. However, it is a core module at Level 6, and therefore not optional, so it is likely that their motivations will be extrinsic.

On the whole, it is likely that the learning orientation of my students is likely to be more extrinsic in nature, which requires that I tailor the modules I teach to fit in with their expectations: in other words help them to pass the module, likely to be with the least amount of work possible. It is also clear that if students lack motivation, the teaching is failing to engage them. While the natures of the assessments are already fixed through validated module specifications, it is possible to teach with extrinsic motivations and engagement in mind, which will be explored further below.

Whose responsibility is it?

Picking up on the point regarding lack of motivation being directly related to the failure of the teacher to engage the student with the teaching and materials, Laurillard makes it quite clear that it is the lecturer’s responsibility to create conditions in which understanding is possible (2002, p. 1). Elder agrees (2012, pp. 6, 9), stating that lecturers have to do everything in their power to deliberately and positively influence and involve learners in every aspect of the learning that we design, and explains that the best way to do so is to be an expert at the ‘act’ of teaching and practise it carefully, mindfully and deliberately, particularly as teaching is one of the most deliberately intrusive acts we can carry out.

To elaborate further, Elder suggests (2012, p. 7) that our teaching repertoire needs to encompass a wealth of well-considered and thoughtful ‘interruptions’, and that we need to be mindful of why, when and how we deliver our interruptions. Beard and Senior (1980, p. 3) confirm that interrupted tasks, if considered worthwhile, are considerably more likely to be remembered and returned to by students than completed ones, in response to the idea that each class period should end with a full resolution of whatever issue was under study.

It appears quite clear that such interruptions are essential when teaching. However, what is meant by ‘interruptions’? Elder states that interruptions occur when we interrupt learners’ conversations, thoughts and actions so that we can redirect their attention to what we need them to learn (2012, p. 6). From that perspective, it appears logical to argue that such ‘interruptions’ are influenced by the various ways of teaching, and studies have contributed helpful explanatory concepts that have become incorporated into practical ideas which deal with learning in whatever environment it takes place, and while their effects are often indirect, when combined with practical experience, these methods begin to acquire meaning and relevance (Jacques and Salmon, 2007, pp. 50-1).

The ‘interruptions’ (types of learning) that we will concentrate on during this paper are problem-based learning, self-directed learning and active learning, underpinned by constructivist and cognitive theories (see below).

Understanding learning

Before embarking on a study of the learner journey, it would be prudent to establish some of the definitions for terms that will be referred to during the course of this paper, namely ‘learning theories’, ‘learning styles’ and the various types of learning.

Learning theories

Schwartz (2001, pp. 365) helpfully summarises the three major learning theories: behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. He also explores, rather helpfully in the present context, the implications of these theories for designing law school instruction.

Behaviourist theory suggests that learning occurs when the learner exhibits the proper response to a specific environmental stimulus, and behaviorism is important to law school instruction because law students must acquire knowledge of the relevant doctrine and policy (Schwartz, 2001, p. 371). Jordan et al (2008, p. 21) argue that this results in a change in behaviour which is always observable, with some behaviourists positing that if no observable change happens, then no learning has occurred. My teaching conforms to behaviourist theory simply because I teach the relevant doctrine for each of the modules I teach: corporate law including types of corporation, the doctrine of ultra vires, capital and financing, the separate legal personality and lifting the veil of incorporation, employment law including employee status, the contract of employment, dismissal and discrimination, and legal theories ranging from legal positivism to natural law and critical race theory to feminist legal theory.

The cognitivist models use a set of theories, called “information processing theories,” which explain how the brain processes and retains learning. Cognitivists equate learning with the learner’s active storage of that learning in an organised, meaningful, and useable manner in long-term memory (Schwartz, 2001, p. 371-2), and Schwartz argues that there are five additional principles relevant to the design of law school instruction: firstly, learning experiences that allow and encourage students to make connections between previously learned material and new material; secondly, the structuring, organising, and sequencing of information to facilitate optimal processing such as course outlines or charts showing the hierarchies in the materials being studied; thirdly, teaching materials that allow students to learn to become active participants in their own learning, that is, to be expert at metacognition (the set of learning and study skills which encourage learners to be introspective, conscious, and vigilant about their own learning); fourthly, teaching learners the internal, mental processing methods necessary to perform observable tasks; and finally, by presenting information graphically (2001, pp. 375-379).

I have adopted the flagging tool (Gibbs, Habeshaw and Habeshaw, 1987), which essentially explain to students what I am doing and why at the outset of every lecture before bringing the lecture to a close. I also provide a slide which details what students are expected to do next, such as listen to the lecture again on Blackboard (via Panopto, the University of South Wales’ (USW) lecture capture system), read the recommended reading and prepare for next week’s workshop. These allow learners to make connections between previously learned material and new material, and to process how the module is structured and organised.

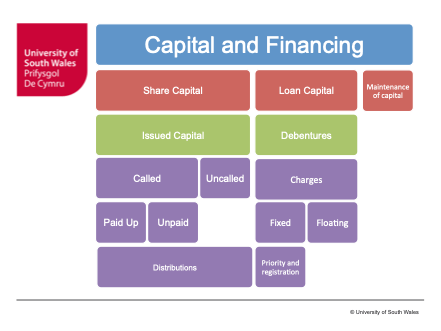

I also routinely teach or remind students how to answer problem questions, deliver presentations or structure assignments, and regularly use graphics to provide “at a glance” information. For example, in Corporate and Business Law, for the topic of capital and financing of companies which is split into three main areas: share capital, loan capital and maintenance of capital, I created the slide at Figure 1 providing an overview of the topic, with similar slides representing each of the areas. I also use a flowchart in Employment Law to illustrate the relationship between unfair dismissal and wrongful dismissal (see Figure 2), thus providing students with cognitively absorbable material.

Constructivism differs from behaviourism and cognitivism because it focuses on the relationship between the mind and the environment. Constructivists do not believe instructors transmit knowledge of “the real world”; rather, they believe each learner continually constructs and reconstructs her own images of what the world is “like” from her experiences and her interpretations of those experiences. Three factors are crucial to learning: practice in real settings (experience), the opportunity to develop personal interpretations of experiences (construction of meaning by the learner), and the opportunity to negotiate meaning (collaboration) (Schwartz, 2001, p. 380).

While practice in real settings is not always practical in the context of teaching law (although USW does have the Legal and Financial Advice Clinic, through which I supervise students advising clients), students are provided with the opportunity to develop personal interpretations of experiences through case studies and problem questions, and also to collaborate with peers in order to negotiate meaning. A solution to the lack of ‘reality’ in teaching law is problem-based learning, which is explored further below.

It is clear from this section that there is evidence of the behaviourist, cognitivist and constructivist theories in my teaching.

Learning styles

It is important to consider students’ learning styles in any consideration of teaching practice. The reason it may be useful for students (and conversely, lecturers) to understand their learning style(s), is because “when a learner does not realise that there are different approaches to learning that might be chosen, or when they might have been encouraged always to work in one particular way, learning might prove difficult” (Pritchard, 2008, p. 18). It is argued that if a preferred style of learning can be recognised and steps taken towards making use of what has been recognised, it is possible that learning might proceed more smoothly and with consequent improved results (Pritchard, 2008, p. 18). Therefore, an understanding of different learning styles can be used to influence the various methods and techniques employed in teaching for the benefit of each student possessing a particular learning style.

Learning styles are generally considered to be the different methods of learning or understanding new information (Entwhistle and Ramsden, 1983, p. 26), the way a person takes in, understand, expresses and remembers information, that is, their mode of problem solving, thinking, perceiving and remembering (Cassidy, 2004, as cited in King, 2011, p. 5). Learning styles go some way in helping us to understand the learner, and there is a significant body of literature that suggests that different students have different styles of learning in which they learn more effectively (King, 2011, p. 5). By way of example, Reid (2005, pp. 61-3) refers to Kolb’s experiential learning model, Honey and Mumford’s learning style questionnaire, Gregorc’s model, the Dunn and Dunn learning styles model, and Given’s five learning systems. In addition, there is also the VARK and Grasha-Riechmann learning styles.

For the purpose of this paper, we will focus on the Honey and Mumford and Grasha and Riechmann learning styles. As I am unable to extrapolate data from students themselves as to their learning styles due to time constraints, I propose instead to establish my own learning style(s), and explore how these are echoed or reflected through my teaching practice, thus establishing what learning styles these practices may benefit most in students.

Honey and Mumford

Honey and Mumford identified four distinct learning styles or preferences: Activist, Theorist; Pragmatist and Reflector. These are the learning approaches that individuals naturally prefer and they recommend that in order to maximise one’s own personal learning each learner ought to understand their learning style and seek out opportunities to learn using that style (University of Leicester, no date).

It appears that I am above all, a Reflector (13), although my scoring suggests that I also demonstrate the traits of an Activist (10), Theorist (9) and Pragmatist (8). A Reflector learns by observing and thinking about what happened, may avoid leaping in and prefer to watch from the sidelines, prefer to stand back and view experiences from a number of different perspectives, collecting data and taking the time to work towards an appropriate conclusion (University of Leicester, no date). This suggests that my preferred learning styles vary according to the task at hand, and some may say fortunately, means that I can learn (and conversely, teach) in any manner of ways. This is probably a reflection of my own learner journey, having attained an honours degree in History, followed by a Postgraduate Diploma in Law and then Legal Practice, and a LLM masters in Law of Employment Relations, and currently undertaking a doctoral degree.

Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Styles Scale

Grasha and Riechmann established six learning styles: Competitive, Collaborative, Avoidant, Participant, Dependent and Independent, and it was developed to measure learning preferences of adults, undergraduate and above; it measures cognitive and affective behaviours of students instead of perceptual (Rollins, 2015).

After completing the Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Style Scales General Class Form (available at http://www.angelfire.com/ny3/toddsvballpage/Cognitive/GR.pdf), it would appear that I have a preference for being a Participant, with a mean score of 4, compared to a learning scale norm of 4.21 for my age group (34-40), and an Independent, with a mean of 3 compared to a norm of 3.42. A Participant is defined as someone who prefers lectures with discussion (such as buzz sessions), opportunities to discuss material, class reading assignments (such as those assigned students in Corporate and Business Law and Employment Law) and teachers who can analyse and synthesise information well (such as the diagrams and illustrations on slides (see above), and I often try to convey the “bigger picture” for each of the topics for students’ (and mine) benefit). An Independent prefers independent study, working alone, self-paced instructions, assignments that give students a chance to think independently, and student-centred rather than teacher-centred course designs. These results are interesting, as they do appear closely aligned to my preferred teaching strategies.

Types of learning

By and large, the various types of learning are split into two categories: learning and the status quo, and learning and change, which are summarised in Figure 1 (Jarvis et al, 2003, 73-74):-

| Theorists | Learning and the status quo | Learning and change |

| Argyris and Schön | Single-loop | Double-loop |

| Botkin et al | Maintenance | Innovative |

| Brookfield | Non-critical | Critical |

| Freire | Banking education | Problem-posing education |

| Jarvis | Non-reflective | Reflective |

| Knowles | Pedagogy | Andragogy |

| Mezirow | Formative | Transformative |

| Instrumental | Emancipatory | |

| Marton and Säljö | Surface | Deep |

Jarvis et al (2003, p. 72) argue that the different types of learning listed in Figure 1 are, fundamentally, the same sets of processes that can be divided into two subsections: the status quo whereby the learner is seen to be treating the external world as objective and that the sole task of learning is to be able to recall accurately that external reality, and change; learning that recognises that it is not the external reality that has to be grasped by learners but that it has to be understood, and only when that happens can any change of any type in the learner occur. Without change, the potential of the individual learners is inhibited, but when there is freedom to learn, learners have more freedom to develop their own potential (Jarvis et al, 2003, p. 75).

This ties in somewhat nicely with Vygotsky’s cognitivist theory, whereby he argues that the developmental process of individuals lags behind the learner process; this sequence then results in zones of proximal development, which is the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers (Vygotsky, 1978, pp. 86, 90). Vygotsky further argues that the traditional view is that when an individual assimilates the meaning of a word or masters an operation, their developmental processes are completed, but in fact, they have only just begun at that moment. Therefore, it is not enough to simply reinforce the status quo (akin to the meaning of a word or mastering a skill), but to instigate a change in the learner so that that external knowledge or ability becomes internalised (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 91), thus the potential of learners to grow and develop occupies a significant place in learning theory (Jarvis et al, 2003, p. 41).

Therefore, the aim of learning through teaching must be to internalise knowledge (according to Davenport (1996) and Allee (1997) ‘knowledge’ is professional intellect, such as know-what, know-how, know-why, and self-motivated creativity, or experience, concepts, values, beliefs and way of working that can be shared and communicated) in a learner. Having established that, we can focus on pedagogical or andragogical methods that result in a change in the learner. The andragogical method is essentially student-centred approaches to teaching which accepts six general principles: adults need to know the “why” of learning; adults learn through trial-and-error experience; adults should own their own decisions about learning; adults prefer learning that which is immediately relevant to their lives; adults learn better from problem-based than content-based environments; and adults learn better with intrinsic versus extrinsic motivators (Knowles, 1977, as cited in Fornaciari and Dean, 2014, pp. 702-3).

For the purposes of this paper, the methods used, or that I would like to explore further, are as follows:-

- problem-based learning;

- self-directed learning; and

- active learning.

Each of these will be examined in detail and consideration made of how they may instigate a change in the learner. This is particularly pertinent as it has been argued that where there has been no change, there has been no learning (Jordan et al, 2008, p. 21).

Problem-based learning

Problem-based learning is a radical way of putting tasks at the centre where students are given authentic, complex tasks to solve and the tasks are written to get them to get new information, understand it and apply it (Knight, 2002, p. 135). This is argued to be a constructivist type of learning, as students are afforded an opportunity to construct meaning through their own personal interpretation of a problem scenario (Schwartz, 2001, p. 380).

For example, in Corporate and Business Law and Corporate Law, I created a character, Jimmy Davies, who had a business manufacturing and selling wifi kettles, and I led the students through Jimmy’s ‘journey’ through the syllabus, such as deciding which type of business suited him and his product, and the impact contract law, tort, employment law would have on his business, what to do if the company faces financial difficulties, and so on. Jimmy and his colleagues would ask for advice, and I used buzz sessions of various length, ranging from five to 20 minutes, to allow students to formulate their own interpretations of Jimmy and his colleagues’ experiences and to discuss these interpretations with colleagues with the aim of providing them (Jimmy and his colleagues) advice on pertinent issues that arose as we navigated through the syllabus.

As this appears to be a constructive teaching method that should instigate a change, I will be implementing problem-based learning for Employment Law and Law for Managers.

Self-directed learning

All learning is individual, and individual learners should have control of (in other words, should be able to plan or direct) their own learning, with educators usually taking an enabling or facilitating role towards learners, rather than one based on the pedagogic principle of instruction (Jarvis et al, 2003, p. 90). Rather than relying on the instructor to teach, the learner truly is in charge of learning; the instructor simply helps the learner by providing a rich environment from which the learner can learn (Svinicki, 2010, p. 74, as cited in Schwartz, 2001, p. 316).

In Employment Law, previously, the learning materials provided to students consisted of lecture slides, worksheets for workshops and detailed notes for each topic in Word format, all of which were made available for students to download. Having decided that this was very much a “one-way street” method of teaching; while I provided students with the materials they needed to achieve the learning outcomes, it did not give much scope for student engagement with the materials. To that end, while the lecture slides and worksheets remained the same, I supplanted the topic notes directly into Blackboard in the format of brief overview of each topic together with instructions for students to engage in directed study, such as reading and research activities, participating in online discussion boards and taking online quizzes. It remains to be seen whether this will prove to be successful, and using statistic tracking and student feedback, I will review this as the end of the next academic year.

Active learning

Active learning is a continuous process of learning and reflection that happens with the support of a group or ‘set’ of colleagues, working on real issues, with the intention of getting things done, and the aim is that learners learn with and from each other and take forward an important issue with the support of other members of the set (McGill and Brockbank, 2004, p. 11).

Having highlighted in the first paper that discussion can be painful and frustrating for all involved (Lowman, 1995, p. 160), the solution appears to be robust task setting. Knight argues that task setting is teaching (2002, p. 105) and that being a good teacher is about being a good designer of tasks and a sensitive facilitator of student engagement with them (2002, p. 124).

The issues associated with discussion can be combated by providing students with a ‘safe’ environment in which they can make their contributions, utilising technology-enhanced pedagogy. Poll Everywhere is the external tool that I have elected to use for my teaching, which “helps gather live audience or class responses anywhere, anytime”. When students are asked a question in lectures or workshops, they will be given the opportunity to answer in real time using a mobile web page, texting or tweeting, with their responses seen live in a Powerpoint presentation (https://www.polleverywhere.com, no date). The benefit of this is that more students will be able to contribute to buzz sessions during lectures and workshops without having to respond by shouting out in front of the entire cohort (although they can still do so if they wish), and this should improve the student experience by being more interactive, more exciting, more accessible, and above all, active, which should allow students to engage in a continuous process of learning and reflection.

Designated interpreters

In relation to the issue of designated interpreters’ involvement in teaching practice, I conducted an informal survey between February and April 2015 aimed at students who were enrolled on modules/courses that I taught in the academic year 2014/15 to glean their perspectives of being taught through BSL and designated interpreters. While the methodology and results of this survey are considered fully in Part Two of the series, it is pertinent to examine what students said about the impact having designated interpreters thrown into the teaching mix has had (or not) on their learning.

It is estimated that in 2014/15, I taught approximately 240 students on a range of undergraduate, postgraduate and professional modules. That total number includes some students who have been counted twice or thrice, as I taught some of the same students on two or three modules (for example, I taught some MLaw students Law on Trial, Practical Legal Research and Professional Conduct and Regulation, and some LPC students Practical Legal Research and Professional Conduct and Regulation). Of 240 learners, 54 responded to the survey, a return of 23 percent.

96.3 percent of the respondents responded that they were aware that I was teaching through a BSL/English Interpreter (the two students that said that they were not aware either misunderstood the question or did not attend lectures and/or workshops in order to establish this rather obvious fact). 59.3 percent of students stated that the level of intellectual excitement experienced in teaching sessions with me was moderate, that is, reasonably clear and interesting, and on a scale of one (no influence) to five (strong influence), 81.49 percent felt that the fact that I was using a designated interpreter to teach them had little or no influence on the level of intellectual excitement they experienced. With regard to interpersonal rapport, 66.7 percent selected high, that is, they found me extremely warm and open and highly student-centred, while 72.22 percent stated that the fact that I was using a designated interpreter to teach them had little or no influence on the interpersonal rapport.

This suggests that, on the whole, for the majority of students, the fact that I used designated interpreters to teach had little or no influence on my teaching. It can be extrapolated from that fact that this meant that the fact that I used designated interpreters had little or no influence on their learner journey.

Conclusion

In an attempt to understand who or what learners are, the student profiles of each of the modules I taught in the previous academic year were examined, as well as their likely motivations. On the whole, it is likely that the learning orientation of my students is likely to be more extrinsic in nature, which requires that I tailor the modules I teach to fit in with their expectations.

The next step was to understand learning, whereby there was an exploration of the three main learning theories and how they were demonstrated in my teaching practice, what learning styles exist, and the various types of learning that have been utilised in my modules.

With regard to the types of learning, moving forward I propose to combine problem-based learning and active learning with self-directed learning, with students engaging in active learning when taking part in buzz sessions during lectures, dealing with problem scenarios in workshops, and carrying out tasks as they work through the syllabus using self-directed learning tools via Blackboard, USW’s virtual learning environment. These ‘interruptions’ (types of learning) appear to align themselves with the constructivist approach to learning whereby students will be provided with the opportunity to develop personal interpretations of experiences through problem-based learning and active learning through collaboration with peers either in pairs, groups or online via online discussion boards and using Poll Everywhere.

Finally, in determining the impact the use of designated interpreters had on learners’ journeys through my teaching, following a survey of 54 students it can be concluded from the data that they had little or no influence on my teaching and interpersonal rapport with students.

Bibliography

Beard, R.M. and Senior, I.J. (1980) Motivating Students. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2007) Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 3rd edn. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Allee, V. (1997) The knowledge evolution: expanding organizational intelligence. Newton: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Curry, A. (1983) An Organization of Learning Styles Theory and Constructs. American Educational Research Association.

Eble, K.E. (1988) The Craft of Teaching: A Guide to Mastering the Professor’s Art. 2nd edn. London: Jossey-Bass.

Davenport, T.H., Jarvenpaa, S.L., and Beers, M.C. (1996) ‘Improving knowledge work processes’ Sloan Management Review 37, pp. 53-66.

Fleming, N.D. and Mills, C. (1992) ‘Not Another Inventory, Rather a Catalyst for Reflection’, To Improve the Academy, 11, 137-155.

Fornaciari, C.J. and Dean, K.L. (2014) ‘The 21st-Century Syllabus: From Pedagogy to Andragogy’, Journal of Management Education, 38(5), pp. 701–723.

Gibbs, G., Habeshaw, S. and Habeshaw, T. (1987) 53 Interesting Things to do in your Lectures. Bristol: Technical and Educational Series Ltd.

Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Style Scales. Available at: http://www.angelfire.com/ny3/toddsvballpage/Cognitive/GR.pdf (Accessed: 24 July 2015).

Higher Education Academy (2011) The UK Professional Standards Framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education. [Online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/UKPSF_2011_English.pdf (Accessed 20 February 2015).

Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1982) Manual of Learning Styles. London: P Honey.

Hruska-Riechmann, S. and Grasha, A.F. (1982) ‘The Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Style Scales’ in J.Keefe (ed) Students Learning Styles and Brain Behaviour. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals, pp. 81 –86.

Jacques, D. and Salmon, G. (2007) Learning in Groups. 4th edn. London: Routledge.

Jordan, A., Carlile, O., and Stack, A. (2008) Approaches to Learning: A Guide for Teachers. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

King, A. (2011) ‘Culture, Learning and Development: A Case Study on the Ethiopian Higher Education System’, Higher Education Research Network Journal 4, pp. 5-13.

Knight, P. T. (2002) Being a teacher in higher education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Laurillard, D. (2002) Rethinking University Teaching. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Lowman, J. (1995) Mastering the Techniques of Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Marton, F., Hounsell, D. and Entwhistle, N. (eds) (1997) The Experience of Learning. 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.

McGill, I., and Brockbank, A. (2004) The Action Learning Handbook. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Pritchard, A. (2008) Studying and Learning at University. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Ramsden, P. (2003) Learning to Teach in Higher Education. 2nd edn. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Reid, G. (2005) Learning styles and inclusion. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Rollins, M. (2015) Learning Style Diagnostics: The Grasha-Riechmann Student Learning Styles Scale. Available at: http://elearningindustry.com/learning-style-diagnostics-grasha-riechmann-student-learning-styles-scale (Accessed: 23 July 2015).

Schwartz, M. H. (2001) ‘Teaching Law by Design: How Learning Theory And Instructional Design Can Inform and Reform Law Teaching’, 38 San Diego Law Review 347.

VARK Learn Limited (no date) VARK: A guide to learning styles. Available at: http://vark-learn.com/ (Accessed 24 July 2015).

University of Leicester (no date) Honey and Mumford. Available at: http://www2.le.ac.uk/departments/gradschool/training/eresources/teaching/theories/honey-mumford/ (Accessed 23 July 2015).

University of South Wales (no date) LLB (Hons) Law. Available at: http://courses.southwales.ac.uk/courses/41-llb-hons-law/ (Accessed 31 July 2015).

Leave a comment