Introduction

“One learns by teaching; one cannot teach except by constantly learning” (Eble, 1988, p. 9). At the date of submission of this assignment, I will have been teaching for eight months, and in those eight months, I have constantly been learning by teaching.

Since leaving higher education in 2003, I was employed by the Royal Association for Deaf people initially as an Advice Worker and then as a solicitor and legal services manager, and before leaving, as Director of Legal Services. I then commenced employment in 2014 with the University of South Wales (the University) as a Lecturer in Legal Practice, and have been charged to teach a wide variety of subjects at undergraduate, postgraduate and professional level. It is important to note that in my career to date, I have never advised or taught hearing people (apart from those fluent in BSL), and so commencing employment as a university lecturer teaching a mainstream subject has been an entirely new experience for me.

As I am profoundly Deaf (“Deaf” with a capital “D” refers to those born Deaf or deafened in early (sometimes late) childhood, for whom the sign languages, communities and cultures of the Deaf collective represents their primary experience and allegiance, many of whom perceive their experience as essentially akin to other language minorities (Ladd, 2003, p. xvii)) with limited confidence in my spoken English, I find myself in an unusual predicament; I have to rely on a third party, namely BSL/English Interpreters, to act as a medium through which to deliver my teaching sessions to hearing (“hearing” refers to non-Deaf people (Ladd, p. xviii)) students.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to explore the development of my teaching and assessment practice and how such practices have influenced and/or been influenced by the experience of teaching through a third party.

Throughout this paper I will refer to a number of courses/modules that I teach:

- Corporate and Business Law, Association of Chartered and Certified Accountants (ACCA) (Level 6);

- Corporate Law, LLM Law/LLM International Commercial Law (Level 7);

- Employment Law, LLB Law/MLaw/Minor/Major/Erasmus (Levels 5 and 6);

- Law for Managers, BA/BSc Business (Level 6);

- Law on Trial, LLB Law/MLaw/Minor/Major/Erasmus (Levels 5 and 6); and

- Professional Conduct and Regulation and Practical Legal Research, Legal Practice Course (LPC)/MLaw (Levels 6 and 7).

Interpreting

A basic Google search suggests that there is little or no evidence of a Deaf person teaching through BSL. A literature review reveals that most of the research conducted of this nature is focused on the experiences of d/Deaf students being taught by hearing lecturers at higher education level, as opposed to the experiences of hearing students being taught by Deaf lecturers.

Of pertinent relevance is Campbell, Rohan and Woodcock (2008) who focus on academic and educational interpreting from the other side of the classroom, that is to say, from the point of view of Deaf academics, which provides an illuminating insight into how Deaf academics should work with their designated interpreters (“designated interpreting” is defined as a marriage between the field of interpreting and the Deaf professional’s discipline or work environment (Hauser and Hauser, 2008, p. 4)). As the BSL/English Interpreters are, in effect, designated interpreters, they will be referred to as such henceforth.

Due to the limited amount of research in this area, I intend to firstly conduct a series of informal surveys at a later date with Deaf individuals who are teaching hearing students (or may have taught hearing students in training) – identified through my contacts in the Deaf community – to ascertain what experiences they have had in teaching through BSL/English Interpreters, so that I may compare these with my own. Secondly, I will direct a series of questions directed at my three designated interpreters based on their experiences of interpreting for me in an academic context. These views will be considered in Part Two of the series.

The Learner Journey

Laurillard makes it quite clear that it is the lecturer’s responsibility to create conditions in which understanding is possible, and the students’ responsibility to take advantage of that (2002, p. 1). In order to do so, consideration has to be given to the concept of ‘surface’ and ‘deep’ approaches to learning which originated in Sweden with Marton and Säljö’s studies at Gothenburg University (cited in Ramsden, 2003; Biggs and Tang, 2007).

The surface approach is concerned with students who appear to be involved in study without reflection on purpose or as part of a strategy, with the focus of that study being on the words, the text, or the formulae, and the deep approach is where students aim to understand ideas and seek meanings, and have an intrinsic interest in tasks and an expectation of enjoyment in carrying it out (Prosser and Trigwell, 1999, p. 3). Ramsden (2003, p. 45) argues that these approaches to learning are not something that a student has; they represent what a learning task or a set of tasks is for the learner, and that everyone is capable of both deep and surface approaches from early childhood onwards.

When examining teaching and assessment practice, consideration will need to be given as to whether these practices promote a surface or deep approach to learning from the student perspective. In relation to the issue of designated interpreters’ involvement in teaching practice, I will conduct a further informal survey aimed at students who are currently enrolled on modules/courses that I teach to glean their perspectives of being taught through BSL and designated interpreters for Part Three of the series.

Language

Before examining teaching style, it is necessary to consider the language that I use during lectures. In general terms, I use BSL. BSL is a full human language, just like any other (Sutton-Spence and Woll, 1998, p. 20). However, when teaching, and in particular as I am teaching law, oftentimes I will find myself using Sign Supported English where I sign the key words of a sentence with the main vocabulary being produced from BSL but much of the grammar is English on the mouth (Sutton-Spence and Woll, p. 16).

For instance, when referring to phrases such as “the veil of incorporation”, “as far as reasonably practicable” and “failure to make reasonable adjustments”, it is not possible to relay these in BSL without distorting their originality which could lead to the students becoming confused as to what it is I am referring to. The situation is further compounded when referring to Latin phrases such as res ipsa loquitor or volenti non fit injuria. As a result, I will use Sign Supported English instead. Therefore, even if no lexicalised sign exists (lexicons are the signs that form the mental vocabulary of a language, which everyone agrees has a certain meaning (Sutton-Spence and Woll, p. 8)), I might choose to borrow the English word into BSL and fingerspell the lexical item, as well as paraphrasing with explanation, to ensure that the audience is accessing the subject-specific vocabulary and its meaning (Napier, 2002, p. 3).

The impact of using BSL (and how the complexity of legalese is dealt with in this context) and designated interpreters will be explored further in Part Two, and has been mentioned here by way of an introduction to the potential issues that may crop up through teaching and assessment practice.

Teaching

What is teaching?

“‘Teaching’ … refer[s] to all the planning, preparation and other activities that teachers do to help student learning” (Knight, 2002, p. 1). Ramsden also states that the “aim of teaching is simple; it is to make student learning possible” (2003, p. 7). These quotes neatly sum up my understanding of what teaching is. The main purpose of a lecturer is to enable students to learn the subject that the lecturer teaches.

Light and Cox (2001) state that lecturers should take care to be heard by everyone, make eye contact with the whole student group, use humour, anecdotes and illustrations, stress important points, and be prepared to be flexible and change/add/delete aspects of the lecture. Lowman (1995) states that actual delivery should have a sense of immediacy, as if the speaker is sharing for the first time his many thoughts with the students, that lecturers must not only capture but also hold students’ attention throughout every class meeting, listen carefully to what students say in order to comprehend what they really mean and that without listening carefully, it can be difficult to remember and summarise students’ comments for class, and give careful and complete attention to discussion, noting essential point(s) in each comment and way students feel about topic (from associated non-verbal messages). The pressure on me as a lecturer to achieve outcomes such as these are compounded by my being Deaf as it inevitably impacts on my ability to teach by virtue of the limitations posed by the fact that I cannot hear.

Setting these issues aside for now (they will be considered fully in Part Two), Biggs and Tang state that one step towards improving teaching is to find out the extent to which lecturers might be encouraging surface approaches in their teaching (2007, p. 44). This suggests that as I have now identified that I might be encouraging surface approaches in my teaching, I can take the necessary steps to reduce or avoid altogether students adopting surface approaches. One such step would be to ensure that my design for teaching is constructively aligned with the nature of student learning as teaching and assessment methods often encourage a surface approach (Biggs and Tang, 2007, p. 23). Constructive alignment is defined as “a marriage between a constructivist understanding of the nature of learning and an aligned design for teaching that is designed to lock students into deep learning” (Biggs and Tang, 2007, p. 54), and in order to do so, it is necessary to phrase the learning outcomes that are intended by teaching those topics not only in terms of the topic itself but also in terms of the learning activity the student needs to engage to achieve these outcomes (Biggs and Tang, 2007, p. 52).

It is clear to me at this conjecture that my teaching practice can and should be improved, but this comes with a warning: improving teaching is often seen as the process of acquiring skills such as how to lecture, run small groups, set assignments etc., but effective teaching is not about acquiring techniques like this, it is understanding how to use them that takes constant practice and reflection (Ramsden, 2003, p. 10).

To date, teaching has been restricted to two main domains: the lecture and the workshop. The lecture has also been referred to as a “briefing session” (on the LPC) and the workshop to a “tutorial” (in Law for Managers) or “practice session” (also on the LPC). For the purpose of this paper, I consider briefing sessions to be the same as lectures, and tutorials and practice sessions the same as workshops.

Lectures

Eble advises lecturers not to lecture (1988, p. 68), which is somewhat ironic given that the verb “lecture” is from whence the title of lecturer is derived. Available research consistently concludes that lectures are one of the least effective methods of conveying information (Lowman, 1995, p. 133). Nonetheless, given the popularity of lectures as a forum for the teaching of a subject, with Light and Cox (2001, p. 97) stating that the “lecture and lecturing is almost synonymous with what higher education is all about” and “assuming adequate space, voice and technology, the lecture can ‘teach’ the student multitudes”, it will come as no surprise that most of my teaching is in the form of a lecture. Light and Cox argue (2001, p. 102) that there are two models of learning through lectures: transmission and engagement, whereby transmission focuses on the information or material of the lecture almost exclusively (see Figure 1),

and engagement focuses on the lecturer as a person committed to engaging with other people in a dialogue concerning particular material (see Figure 2).

It is argued that the transmission model adopts a surface approach to learning, whereby the engagement model adopts a deep approach. Therefore, if the engagement model is utilised, then Eble’s advice need not be heeded.

The key to engaging students in lectures is preparation. In order to make lectures more engaging, Light and Cox suggest that the design of the lecture needs to take into consideration the reasons why the lecture is being employed and what its role is within the overall learning and teaching context in which the lecture is situated (2001, p. 103). The preparation of lectures has clearly influenced my delivery of them. Of the eight modules I teach, I inherited PowerPoint slides and other materials for seven of them. After six months of teaching, the lectures that were more successful from my perspective (in terms of flow, comfort with the subject matter etc.) were those that I prepared from scratch or almost from scratch (hereby referred to as ‘substituted lectures’), as opposed to those that I replicated from the previous academic year’s teaching (to be referred to as ‘replicated lectures’). In essence, the preparation of the substituted lectures allowed me to design the lecture from the perspective of the engagement model, as I then designed a lecturing ‘voice’ or ‘mode of being’ which integrates material, students and self (Light and Cox, 2001, pp. 104). For instance, I developed a habit of creating illustrations that provided an overview of the entire topic at a glance to assist students in grasping the context of each of the various elements involved in that topic.

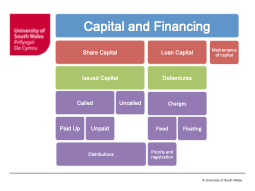

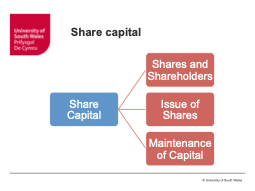

For example, in Corporate and Business Law, the topic of capital and financing of companies is split into three main areas: share capital, loan capital and maintenance of capital. In the inherited slides, there was no such “at a glance” tool. Instead, there was a series of slides looking at each area and the subdivisions within each area, with no contextualisation or “bigger picture”. In the substituted lecture, I created the slide at Figure 3 providing an overview of the topic, with similar slides representing each of the areas (see Figure 4 for an example in relation to share capital), and where appropriate, utilising a particular section of Figure 3 and annotating with useful information for the student group which I then referred to/elaborated on during the course of the lecture (see Figure 5). These illustrations are examples of how Light and Cox’s lecturing ‘voice’ or ‘mode of being’ can be brought to the fore (Light and Cox, 2001).

As can be seen, by utilising the engagement model, lectures need not be a lost cause. Indeed, various teaching methods have been developed to address the ineffectiveness of lectures, such as flagging, reviews, buzz groups, problem-centred and syndicate groups and pyramidding (Gibbs, Habeshaw and Habeshaw, 1987) to name a few.

When preparing for Corporate and Business Law, which commenced the first week of September 2014, I was of the view that the three-hour lecture materials were going to ineffective, so I took it upon myself to research teaching methods, and as a result, I introduced buzz sessions into my lectures. A buzz session, or a buzz group as they are referred to by Gibbs and Habeshaw (1989, p. 53), from whence the idea came, requires students to form pairs or threes, to set a specific question or topic to be discussed for a minute or two, and to do this every fifteen minutes or so.

Buzz sessions were utilised to great effect in Corporate and Business Law as the students who took this module achieved a 90 percent pass rate in their (external) exam in December 2014. Buzz sessions were also used in Law for Managers, although I found them less effective mainly due to the lack of engagement in the sessions by the students, although one student in their reflective journal (which had to be submitted as part of their written assignment), did remark: “[t]he Buzz sessions were the most interesting part of the lectures. Sitting in groups and discussing a concept enhanced my retention capacity and made the lecture lively”. It appears that they were more effective than I had thought and in hindsight, I should have persevered with the buzz sessions. Interestingly, for Employment Law, I did utilise buzz sessions at the outset, but as the academic year wore on, I realised that I was not incorporating them into my lectures. The reason was again lack of engagement in the sessions by the students, and so I must have inadvertently reverted back to the transmission model. Again, I should have persevered.

I also adopted the flagging tool (Gibbs, Habeshaw and Habeshaw, 1987), which is essentially explaining what I am doing and why. At the outset of every lecture, I provide students with a slide detailing an overview of the lecture and before bringing the lecture to a close, provide a slide detailing what will be covered in the next lecture, in line with Eble’s advice to provide an ending for every lecture and maintain a continuity with what has gone before and what lies ahead (1988, p. 81). I also provide a slide which details what students are expected to do next, such as listen to the lecture again on Blackboard (via Panopto, the University’s lecture capture system), read the recommended reading and prepare for next week’s workshop. In hindsight, I could be more explicit in my instructions, particularly as I do not specify what the recommended reading is, and also do not generally provide guidance as to what students need to do in order to prepare for the workshops.

Another approach I have utilised is that afforded by problem-based learning. Problem-based learning is a radical way of putting tasks at the centre where students are given authentic, complex tasks to solve and the tasks are written to get them to get new information, understand it and apply it (Knight, 2002, p. 135). For Corporate and Business Law, I created a character, Jimmy Davies, who had a business manufacturing and selling wifi kettles, and I led the students through Jimmy’s ‘journey’ through the syllabus, such as deciding which type of business suited him and his product. Jimmy and his colleagues would on occasion ask for advice, and I used buzz sessions to allow students to provide Jimmy and his colleagues with advice on pertinent issues that arose as we navigated through the syllabus. I am now utilising the character of Jimmy in the Corporate Law module.

Interestingly, I have not adopted this problem-based learning to great effect in workshops, so this is something for me to consider. I can see the approach having particular benefit for the Employment Law and Law for Managers modules. For Employment Law, I intend to create a large fictional corporation which employs 3,500 staff and the whole module will then focus on employment law issues within the company that cover all aspects of the syllabus with a whole host of characters with various employment problems.

By way of a final point, I am guilty of including a slide which merely states “Questions?”. Gibbs, Habeshaw and Habeshaw (1987, p. 155) affirm that this is so routinely ineffective that it has come to mean “that’s all for today”. To that end, I have changed the slide to state: “Take two minutes to think of a question” and then “Ask it” for the Corporate Law module which I started teaching this week. It appeared to work, as students did ask questions, and so I will roll this technique out for all lectures.

Discussion

At its worst, discussion is painful and frustrating for all involved, with long silences and the averted faces of students fearing they will be called upon or pressured to volunteer comments, resulting in lecturer’s abandoning the discussion technique after one or two unsuccessful attempts, rationalising that their students just aren’t interested (Lowman, 1995, p. 160). As a lecturer, I too find discussions painful and frustrating. However, rather than abandoning them, I have tested different methods of leading discussions with mixed results. Discussion has been a staple teaching technique for the two one-hour Employment Law workshops and two one-hour Law on Trial workshops I run per week. Lowman (1995, p. 161) goes on to say that discussions must be well planned in order to be effective, and that, interestingly; the quality of the discussions depends on how well the lecturer performs.

From the point of view of the student, the purpose of discussions is to ask students to apply what they have learned in lectures by requiring them to demonstrate their understanding of a particular topic, and the discussion is a safe way for them to “try their wings while the [lecturer] hovers close by” (Lowman, 1995, p. 161). Lowman suggests that 10 to 15 minutes discussions are sufficient to achieve most of the potential benefits from a discussion (p. 166). In most workshops I lead, I allow students to discuss the task at hand for up to 40 minutes. Lowman states that more than 30 minutes of discussion can develop greater intellectual independence, but only among the few speaking students, and is likely to frustrate the majority (1995, p. 167). Thus, it is necessary to revisit this method of teaching.

The techniques I have employed in workshops are as follows:-

- One-hour of self study either individually or in groups, working through the questions set;

- A 30 minute discussion in groups examining a problem question followed by a question and answer session led by me as we work through the material;

- A one-hour question and answer session led by me with intermittent group discussions on specific issues;

- A 30 minute discussion in groups looking at one or two questions allocated by me to each group, with flipchart paper and pen to write down bullet points of their answers, followed by a presentation of around five to ten minutes per group explaining their findings; or

- A 30 minute discussion in groups again looking at one or two questions allocated by me to each group, with instructions to write down the main points from their discussion, and 10 minutes to write them on the whiteboard, with the last 10 minutes utilised by students to either write down (or take a picture on their smartphones) the points from all questions for the purposes of independent study later on.

For each technique (apart from the third), I would usually attend to each group individually to ascertain how they are finding the tasks set and to glean their current thinking so that I am assured that they are on the right track, and also to plant further thoughts in their mind to ponder. To my mind, the least successful of all was the third. I found that rather than allowing students the opportunity to speak, I was impatient and instead was putting forward my thoughts on the specific issues to the extent that it almost became a lecture. This goes back to Lowman’s point that discussions have to be well planned to be successful, and it was lack of preparation that possibly resulted in this outcome, as well as not allowing students time to consider the questions I posed, consult the materials and formulate responses.

The most successful of all these techniques were the first and fifth ones. The first panders to student sensibilities as it means that they are “left alone” and are not required to speak or do anything in front of the entire class. However, I am usually none the wiser as to whether they are achieving the learning outcomes. The fourth, however, also panders to their sensibilities as they can write their thoughts on a particular topic on the whiteboard, and they also have access to other students’ thoughts to ensure that they leave the room having had access to all the information available. The fact that their findings are also displayed on the board allows me to ascertain whether they have achieved the learning outcomes and to identify who may be struggling more than others.

Task setting

Knight further argues that task setting is teaching (2002, p. 105) and that being a good teacher is about being a good designer of tasks and a sensitive facilitator of student engagement with them (2002, p. 124), and so we must consider task setting when examining teaching practice. Knight (2002, pp. 128-131) provides a list of 32 common types of task. To date, only four of the 32 have been deployed during my teaching. I have set small groups of students the task of writing a letter of advice in relation to a problem question (Employment Law) during and after a workshop and then emailing to me for all to critique in the following workshop (action learning sets), and analysing case studies is a prominent task in all courses I teach as problem questions are a primary way of assessing students in their application of the law to a set of facts. Completion tasks are common in Law on Trial, with lecture and workshop materials providing information about a particular topic and setting tasks for students to complete either during the lectures, in workshops or independently. Metacognitive reflection is a task that is set as an assessment in Law on Trial by way of journal reviews and Law for Managers utilises reflective journals. It is argued that the buzz sessions utilised in lectures are also a form of task setting and are closely aligned to completion tasks and analysing case studies. In reflecting on what tasks I have employed through my teaching, I have identified that there are a considerable number of alternative tasks that I could use that I have not yet considered using.

Assessment

Assessment is about getting to know students and the quality of their learning (Rowntree, 1977, as cited in Ramsden, 2003, p. 176), and lecturers can get to know students by labelling and categorising them and by understanding them in all their complexity, considering how their various strengths and weaknesses contribute to what they know, and what these strengths and weaknesses imply for their potential as learners of the subject (Ramsden, 2003, pp. 176-177). Assessments also have to be constructively aligned to the intended learning outcomes and are a type of learning activity (Ramsden, 2003) otherwise, as in the example of a psychology graduate (Ramsden 1984, p. 144, as cited in Biggs and Tang, 2007, p. 23), an inappropriate assessment can allow students to get a good mark on the basis of memorising facts rather than understanding.

Upon reflection, each module that I teach actually utilises different types of assessment and on the whole, I consider these assessments to be aligned to their learning outcomes. The problem question for Employment Law requires students to apply their understanding of a topic that has been taught in lectures and workshops to a particular scenario in the form of an essay which also requires critical analysis of current academic thinking on the topic. The marks awarded ranged from 8 to 73 percent (the average mark was 55 at Level 5 and 50.8 percent at Level 6). The second assessment is a presentation with written arguments affords students the opportunity to demonstrate their understanding as they have to explain to an audience their thoughts in relation to a problem question or an essay question orally. It will be interesting to compare the results of the presentations with the written assignments. There was a 90 percent pass rate for the online multiple choice question examination for Corporate and Business Law which suggests that it is closely aligned to the learning outcomes as it actually tests students’ understanding of the law and legal principles they have been taught. Memorising relevant information would not necessarily result in a pass for this module.

In Law for Managers, the written assignment accounted for 40 percent of the module and the examination 60 percent. Interestingly, the average mark for the written assignment was 52.9 percent, but for the examination, it was 54.8 percent. The written assignment was essay based; the examination was a mixture of problem and essay questions (out of four, three were problem questions). This suggests that problem questions are more closely aligned to the learning outcomes for this module, and I intend to introduce problem questions for the written assignment in the next academic year as the students who obtained the highest marks had successfully applied the law to the problem questions, which suggests a higher level of understanding of the subject matter and conversely, a deep approach to learning.

For Practical Legal Research students are marked Competent or Not Yet Competent, and in their mock examinations, most were marked Not Yet Competent, not because the research they conducted was wrong, but because they had not presented their findings in an appropriate way. In the feedback session following the mock, I briefed the students in how to utilise the report template effectively, and in marking further attempts prior to the main examination, I am noting more students achieving Competent. This suggests that students are able to pass this module just by presenting the information in a certain way, and not necessarily by understanding the topic set. However, they are required to apply the law to the scenario and advise the client. If the advice is wrong, although the report is completed correctly, they would be marked Not Yet Competent.

In Professional Conduct and Regulation, students are allowed to take in two text books with them which in theory contain all the information they require to pass the exam successfully. It is possible for students to just refer to the textbooks and obtain marks, but these marks are negligible, for example, half a mark for referring to a specific Principle, Outcome or Indicative Behaviour, and another half a mark for stating what that Principle, Outcome or Indicative Behaviour is. However, most of the marks are derived from applying these to the facts of the scenario presented.

Upon review of each of the assessments I have inherited, it appears that they are all actually quite closely aligned to the learning outcomes for each module, and only minor improvements or modifications are required moving forward.

Conclusion

Before attempting to conclude this paper, it is necessary to reinforce the message that this paper is the first of three papers, and so a holistic conclusion encompassing teaching practice and the learner journey and the impact the use of a designated interpreter has on both cannot yet be made.

To nonetheless conclude this examination of teaching practice, it is quite clear that Eble’s succinct quote, “one learns by teaching”, is of particular relevance, and that learning to be a lecturer means learning about “one’s own values, self-theories, thoughts and identities as well as gaining other forms of knowledge needed to encourage that valued, complex learning which can involve the student as a whole person” (Knight, 2002, p. 24).

It has been established that the techniques employed in the delivery of lectures (buzz sessions, flagging, and the use of illustrations and diagrams) and workshops (group discussions), discussions, task setting and assessments, have had mixed results. Of significant note is that weaknesses have been identified so that I may improve on the technique going forward, particularly successful techniques will continue to be deployed and enhanced, and new techniques identified through the research for this paper will be attempted.

With regard to the Higher Education Academy’s UK Professional Standards Framework (2011), it has been demonstrated in this paper that I have successfully engaged with the five Areas of Activity (2011, p. 3): designing and planning learning activities and/or programmes of study; teaching and/or support learning; assessing and giving feedback to learners; developing effective learning environments and approaches to student support and guidance; and engaging in continuing professional development by enrolling on the Postgraduate Certificate in Developing Professional Practice in Higher Education. In relation to Core Knowledge (2011), I have demonstrated knowledge of my subject material and I have demonstrated the utilisation of appropriate methods for teaching and learning at undergraduate and postgraduate level and methods for evaluating the effectiveness of teaching.

It is contended that the aims of this paper: to examine and reflect on teaching and assessment practice and their effect on student learning, has been achieved. Now that we have established the effective learning, teaching and assessment practices that I employ in my role as lecturer, we are now in a position to move on to a consideration of how the involvement of designated interpreters in teaching delivery impacts on these practices in Part Two.

Bibliography

Alexieva, B. (2002) ‘A typology of interpreter-mediated events’, in Pöchhacker, F. and Shlesinger, M. (eds.) The interpreting studies reader. London: Routledge, pp. 219– 233.

Eble, KE. (1988) The Craft of Teaching: A Guide to Mastering the Professor’s Art. 2nd edn. London: Jossey-Bass.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2007) Teaching for Quality Learning at University. 3rd edn. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Bligh, D. (2000) What’s the Point in Discussion? Exeter: Intellect Books.

Bramley, W. (1979) Group Tutoring: Concepts and Case Studies. London: Kogan Page.

Campbell, L., Rohan, MJ. and Woodcock, K. (2008) ‘Academic and Educational Interpreting from the Other Side of the Classroom: Working with Deaf Academics’, in Hauser P., Finch, K. And Hauser, A. (ed.) Deaf Professionals and Designated Interpreters: A New Paradigm. Washington DC: Gallaudet University, pp. 81-105.

Gehman, H.S. (1914) ‘The Use of Interpreters by the Ten Thousand and by Alexander’, The Classical Weekly, Vol. 8, No. 2 (Oct. 10, 1914), pp. 9-14.

Gibbs, G., Habeshaw, S. and Habeshaw, T. (1987) 53 Interesting Things to do in your Lectures. Bristol: Technical and Educational Series Ltd.

Gibbs, G. and Habeshaw, T. (1988) 253 Ideas for Your Teaching. Bristol: Technical and Educational Series Ltd.

Gibbs, G. and Habeshaw, T. (1989) Preparing to Teach. Melksham: The Cromwell Press.

Hauser, AB. and Hauser, PC. (2008) ‘The Deaf Professional-Designated Interpreter Model’, in Hauser P., Finch, K. And Hauser, A. (ed.) Deaf Professionals and Designated Interpreters: A New Paradigm. Washington DC: Gallaudet University, pp. 3-21.

Higher Education Academy (2011) The UK Professional Standards Framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education. [Online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/UKPSF_2011_English.pdf (Accessed 20 February 2015).

Knight, P. T. (2002) Being a teacher in higher education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Ladd, P. (2003) Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Laurillard, D. (2002) Rethinking University Teaching. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Light, G. and Cox, R. (2001) Learning & Teaching in Higher Education: The Reflective Professional. Gateshead: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Lowman, J. (1995) Mastering the Techniques of Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Marschark, M. (2005) Sign Language Interpreting and Interpreter Education. ProQuest ebrary [Online]. Available at: http://www.ebrary.com/ (Accessed: 26 December 2014).

Marschark, M. et al (2004) ‘Comprehension of Sign Language Interpreting: Deciphering a Complex Task Situation’, 4 Sign Language Studies, pp. 345-xxx

Napier, J. (2002) ‘University interpreting: Linguistic issues for consideration’, Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 7(4), pp. 281–301.

Napier, J. and Barker, R. (2004) ‘Accessing University Education: Perceptions, Preferences, and Expectations for Interpreting by Deaf Students’, Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 9, pp. 228-236.

Pöchhacker, F. (2004) Introducing interpreting studies. London: Routledge.

Prosser, M. and Trigwell, K. (1999) Understanding Learning and Teaching. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Ramsden, P. (2003) Learning to Teach in Higher Education. 2nd edn. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Salevsky, H. (1993) ‘The distinctive nature of interpreting studies’, Target: International Journal of Translation Studies, 5 (2), pp. 149– 167.

Sedran, D. (2012) ‘Deaf Professionals and Designated Interpreters: A Collaborative Approach to Service Delivery’, Association of Visual Language Interpreters of Canada, 2012 Conference. Calgary, Alberta, 16-22 July 2012. [Online] Available at: http://www.avlic.ca/sites/default/files/docs/AVLIC%202012%20Deaf%20Professionals%20and%20Designated%20Interpreters-A%20Collaborative%20Approach%20to%20Service%20Delivery%20D%20SEDRAN%20J%20DUNKLEY.pdf (Accessed: 17 February 2015).

Stinson, M. and Liu, Y. (1999) ‘Participation of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students in Classes with Hearing Students’, Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, pp. xx-xx.

Leave a comment